Boston College Timelapse from Ryan Reede on Vimeo.

Short timelapse video I shot in a few hours around the Boston College campus.

Boston College Timelapse from Ryan Reede on Vimeo.

Short timelapse video I shot in a few hours around the Boston College campus.

Like it or not, both 3D and Virtual Reality are here to stay. Tech ranging drastically in size and focus are embracing the next generation of immersive experience products such as Oculus VR (acquired by Facebook in March of 2014), Jaunt VR, Google Project Tango, and Matterport.

Man wearing an Oculus Rift virtual reality headset displaying 360 degree footage shot on a Jaunt VR camera system.

Whereas Oculus and Jaunt seem to be concerned with solely the capture and displaying of immersive 360-degree footage however, Google and Matterport’s technology focuses less on what light hits its lens, and more on the loads of spatial data their products’ sensors gather. Both Google and Matterport are working to automate the tedious task of digitizing our physical word.

The Matterport camera atop a tripod

Matterport’s software and hardware development team together since 2011 now has a fully functional camera for sale that uses an iPad-only application for controlling. The form of the Matterport is bulky and awkward, but it shouldn’t be compared to a typical DSLR camera. Instead of just one lens protruding from a sensor within a body, the Matterport has 15 (based on images) parts that are required to be facing the camera’s environment to work. Additionally, there is significantly more on-board data processing that has to go on within the Matterport than on a typical camera so naturally, it will take up more space. Matterport’s frontier technology isn’t cheap either. The camera is $4500 and there are other monthly fees involved for cloud-based data storage and processing.

To generate a 3D .obj file from the physical space around it, the Matterport gets set in a position in a room, and instructed to begin a scan via the connected iPad. The camera then makes a 360-degree spin on its tripod in about a minute then will start processing what it saw in the cloud. Once the data handling from the scan is complete, the iPad will display which parts of the environment were well captured and which were not (due to obstructions such as furniture or distance from the camera) letting the user know where to place the camera for the next scan. Depending on the complexity, size and number of obstructions within the area being modeled, the number of scans required to be done will vary.

While Matterport’s system has produced some impressive sample results as seen on their website they’re up against the big guns: Google is too exploring this type of digital mapping. Matterport’s behemoth Mountain View counterpart is thinking much smaller though. Declassified in February of 2014, Google showed off that it has been working on a similar concept to Matterport, but ported to a mobile device and coined ‘Project Tango.’ Currently distributing their first few hundred prototype Android devices to developers and researchers around the world, Project Tango does seem significantly more promising than Matterport. Even though Matterport’s gear is readily available whereas Google’s is still in the prototyping phase, it’s certainly evident that the future of just about all tech is mobile. Thus Tango is a handheld device unlike the tripod-bound Matterport.

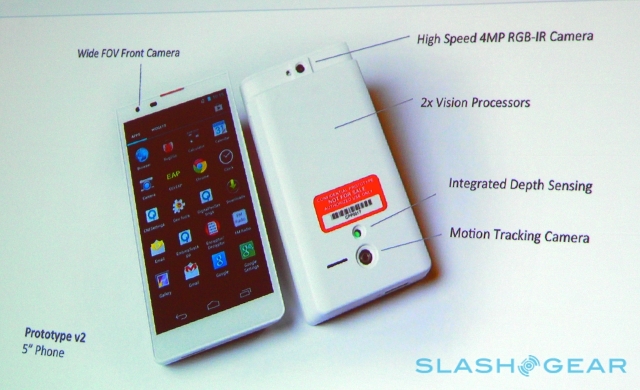

A hardware overview of Google’s Project Tango (via: Slashgear)

Due to Tango’s clear mobility, X, Y, and Z-axis information dealing with position and rotation has to be gathered. When mapping, Google says its device is capturing over 250,000 points of data per second from the devices three cameras and multiple interior sensors. Even though the current Project Tango’s has its “rough edges,” Google is likely making the product on a small device so once those rough edges are smoothed over, any Android device with the right sensors inside can run Tango software.

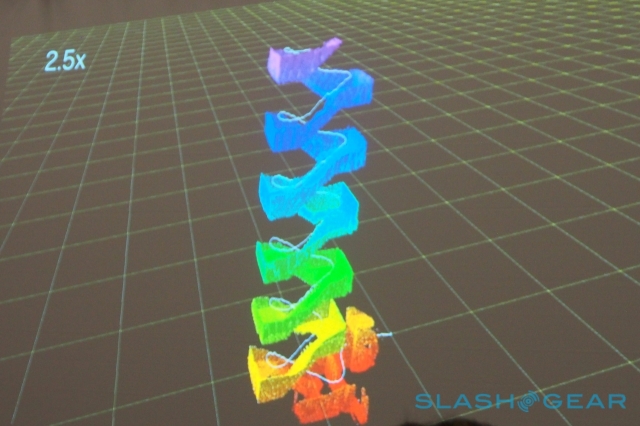

A visualization of the data Tango brings in while mapping a staircase. (via: Slashgear)

Given the rate at which devices are shrinking and how mobile is starting to dominate all of tech, it would seem as though Project Tango is on the better track. Even though they don’t yet have much to show for with their efforts, Google’s focus on something handheld from a user standpoint makes all the sense in the world. Regardless of how digital mapping of 3D environments gets done, its potential use in art, history, real estate, social media, gaming and a plethora of other areas is not going anywhere.

The contrast between free indirect discourse and unbiased narrative viewpoint plays a crucial role throughout James Joyce’s Dubliners. In this vine based on ‘Clay,’ the viewer sees how Maria explains the event on the train vs. how the event likely played out in realty.

For nearly a decade now, Autodesk has remained at the cutting edge of 3D, animation, motion graphics, and video editing software. Known for their incredibly powerful programs that hide behind infinitely less menacing and intuitive interfaces, Autodesk’s iOS application 123D Catch seems quite lacking. Although making software for the casual iPhone or iPad user who wants to play around with a 3D model of their shoe is not (and seemingly never will be) Autodesk’s forte, 123D Catch still could have been much better in many ways. On application launch, there are no directions for the user to know where to begin their first “Capture.” After some toil, the camera screen appears and the application begins to shine. Each iPhone and iPad that is compatible with Autodesk’s free application has two sensors vital to generating the scalable and interactive 3D model 123D Catch promises to generate using only the device’s camera: A 3-Axis Gyroscopic sensor, and an Accelerometer. The gyro outputs data to the application that classifies where each image on a 3D plane was taken from, and at what angle the camera’s lens was facing. The accelerometer isn’t quite as crucial, but it is more sensitive to quick movements made by the device to ensure that before each picture is snapped, the camera is steady and the resulting capture won’t be blurry.

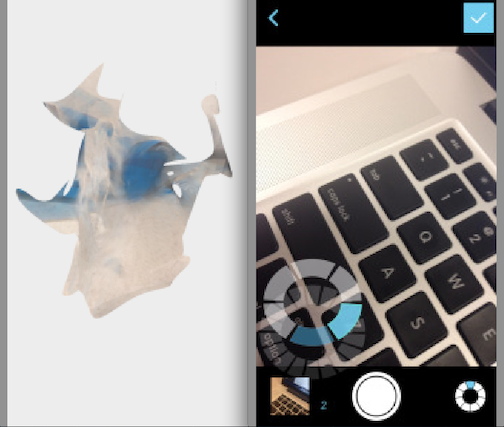

Although the model often comes out looking like a blob, 123D’s Camera interface shows the spatial alignment of each image during capture.

After directing the user to snap anywhere from 10-40 images from various angles and heights of whatever it is they want to make a 3D model, 123D Catch disappoints once again. Before being able to play with their model, the user is forced to making an Autodesk account with their email address and all. After feeling as though they have invested too much time into their model, the user reluctantly obliges and joins Autodesk’s database. But then, instead of being able to view their model, the app uploads each of the user’s pictures to Autodesk’s servers where the model is to generated. This is not a quick process however. Although there will be variation in time depending on server traffic and complexity of the object, it isn’t until around 30 minutes after upload that the model is ready to be used. Even then, there no guarantee that the model will be accurate. Although the scaling and zooming is smooth and simple, it is worthless when the model you wanted comes out as a blob. Strong lighting and plain backgrounds help the app tremendously.

Hardware startup 360Fly is looking to blaze a trail that other wearable imaging companies such as Sony and GoPro have yet to step foot on: 360° video. Seemingly in the middle to late stages of product development and slated for a Summer 2014 release, 360Fly promises a light (120g), compact and spherically-shaped camera with an upward-facing lens. Although no sample footage from the camera is available to interact with yet, the video quality will certainly have to be impressive in order to compete with GoPro’s 4K sensor. If by release the 360Fly can offer quality high-definition resolution along with the 360° horizontal by 240° vertical field of view the camera is already receiving praise for, this will be an incredible piece of hardware. If the software too is as intuitive and smooth as their teaser video makes it out to be, then the issue of not being able to interact with what you have shot (currently no software is available to view/edit 360° video) would be laid to rest.

Pending a successful Q3 2014 launch for 360Fly, the camera’s applications will be far-reaching. Giving the the viewer more creative control over how they receive content is certainly up the road for cinema and especially broadcast TV. The world of action sports will flock to to the waterproof (up to 5m) 360Fly in troves despite its $450 MSRP and even the real-estate and interior design industries could benefit from it.

Check it out here.

Although James Joyce’s sensory-detail heavy writing style remains consistent throughout his famed collection of short stories entitled Dubliners, one specific tale takes this style above and beyond. Araby, the tale of Joyce’s young boy narrator who travels to the bazaar for his love, is arguably written more with a screenplay feel than simply a short story. A quality of most narrative writing is to paint an image in the mind of the readers. In Araby however, Joyce presents not just images—at some points a fully framed scene lit and blocked can be extrapolated from his text.

On set, the role of the cinematographer is to create and uphold a vision for the overall look of a film. Expertise in camera work is obviously vital, but understanding how to work light is equally as crucial. In the following quote from Araby, Joyce outlines the look for his vision of Mangan’s sister: “The light from the lamp opposite our door caught the white curve if her beck, lit up her hair and rested there and, falling, lit up the hand upon the railing.”

Similar to how the director of photography’s notes read in a screenplay, Joyce describes the light in the scene from Araby — from where it originates, the color temperature, and how he plans for it to hit the subject. This example isn’t the only instance in Araby which Joyce’s writing styles come off as more cinematic than literary. The manner in which Joyce describes the beginning of the young boy’s train ride to the bazaar has a similar sequential and movie-like feel.

Cinematographer on set

“The train moved out of the station slowly. It crept onward among ruinous houses and over the twinkling river.” The way Joyce uses concise, yet visceral sentence structures makes the short story read like a movie plays out. The scene would start with a shot of the creaky train pulling out of the station before cutting to a moving point of view shot looking out among homes and a waterway glistening under the moon and stars. Throughout James Joyce’s Dubliners, and more specifically in Araby, the writing transcends what is typical for a short story. It’s far more descriptive regarding light giving it the feel of a cinematographer’s journal.